There are various theories that explain the mystery behind the evolution of an individual as a child sexual abuse offender. Biological theories propose that abnormalities in physiological factors like sex hormone levels or chromosome makeup make an impact on abusive sexual behaviour. In fact, sex hormones like androgens and testosterone regulate the sexuality and aggression of an individual (John Jay College of Criminal Justice & Catholic Church, 2004, p. 163). That is why in puberty, when there is a dramatic increase in sex hormones; individuals specifically find it difficult to live with their aggression and sexuality. Some empirical studies found elevated testosterone levels among markedly aggressive sex offenders (Marshall & Barbaree, 1990, pp. 258–260). There is a defective chromosomal condition called Klinefelter syndrome (XXY chromosomes). It is characterized by a normal male physical build with large extremities, a small penis, and rudimentary testes. At the onset of puberty, affected individuals do not usually acquire the secondary sexual characteristics of a male (Saleh & Berlin, 2011, p. 64); 80% of such males display both hormonal and physical characteristics of a female. They experience problems with sexual orientation, erotic desires and various sexual deviations. This genetic defect can also lead a person to child sexual abuse (John Jay College of Criminal Justice, 2004, pp. 163–164).

Developmental theories specify the interrelation between childhood experiences and one’s sexual deviation. Sexual victimization as a child may increase the risk of a victim becoming an offender (United States General Accounting Office, 1996, p. 5). Childhood emotional abuse and family dysfunction were found to be common risk factors for different paraphilias, including paedophilia (Lee, Jackson, Pattison, & Ward, 2002, p. 73). Empirical studies on child sexual abuse offenders identified the common presence of a hostile family atmosphere, frequent punishment and aggressive drunken fathers. An aggressive father would become a role model for some children to become aggressive and they would develop a negative attitude towards women. Some children found it difficult to identify with such parents and become insensitive adults without any empathy or regard for the rights of others, leading them to isolation in socio-sexual interactions. Poor socialization and violent parenting style also damage their self-esteem. Separating sex from aggression or living sex and aggression in a healthy manner becomes difficult for them and they learn to solve problems by using violence (Marshall & Barbaree, 1990, pp. 260-264).

Attachment theories find an interrelation between attachment defects and child sexual abuse behaviour. Lack of a proper attachment to parents limits the possibility of a strong and positive attachment in adolescence and adulthood. It creates an intimacy deficiency, leading to emotional loneliness and a tendency to alienate individuals. Such males would lack interpersonal skills and social adequacy, naturally restricting the possibilities of a normal intimate relationship with girls in late adolescence. Isolation increases anxiety and stress, creates hostility towards females and may lead one to child sexual abuse (Marshall & Barbaree, 1990, pp. 262–263). Attachment styles in adulthood can be divided into four types based on the combination of one’s self-image and the image of the other person: secure, preoccupied, dismissing and fearful (Bartholomew & Horowitz, 1991, pp. 226–227). Among these four, those people with preoccupied attachment styles- negative self-image and positive image of others- would characteristically develop deviant relations with children (John Jay College of Criminal Justice & Catholic Church, 2004, p. 165).

Behavioural theorists explain this deviant behaviour as a learned condition, just as one learns the conventional mode of sexuality. There are two parts to this model: an acquisition process and a maintenance process. This maladaptive behaviour of child sexual abuse may be the result of abuse history in childhood or repeated sexual activities. Sex offenders reported a greater use of different types of sexual activity to cope with stressful situations than non-sex offenders (John Jay College of Criminal Justice & Catholic Church, 2004, pp. 164–165, Cortoni & Marshall, 2001, p. 27). A study of child sexual abuse offenders shows that 92% of recidivist offenders had been previously convicted at least once for non-sexual offences of an antisocial nature (Smallbone & Wortley, 2004, p. 175). The misleading messages in society through mass media and different internet facilities, like pornography, favour the formation of such abusive behaviour (Marshall & Barbaree, 1990, pp. 264–266). Some contributory factors, like excessive intoxication by alcohol or drugs and anonymity in large cities, facilitate a mental disposition, even in normal people, by overcoming the inhibitions to commit an immoral or criminal act (Marshall & Barbaree, 1990, pp. 269–270).

Cognitive-behavioural theorists stipulate a ‘neutralization’ process like rationalization or justification among child sexual abuse offenders. These conscious or unconscious processes can be called ‘cognitive distortions’. They enable the offender to escape from feelings like shame and guilt and from self-blame and responsibility for deviant sexual activity. They naturally encourage them to continue their offending behaviour (John Jay College of Criminal Justice & Catholic Church, 2004, pp. 165–166). These distortions can be about the nature of the victims, or society or about themselves, and they reinterpret the situation. They usually emerge from their underlying desires (Ward & Keenan, 1999, pp. 821–832). Due to these cognitive distortions, offenders usually misread the social cues and the emotions, like fear and anger, of their victims, and would interpret a child’s friendly behaviour as an invitation for sex (The John Jay College of Criminal Justice, 2004, pp. 166–167). A comparative study between child molesters and non-offenders recognized severe cognitive distortions among child molesters regarding sex between an adult and a child (Marshall, Marshall, Sachdev, & Kruger, 2003, p. 171).

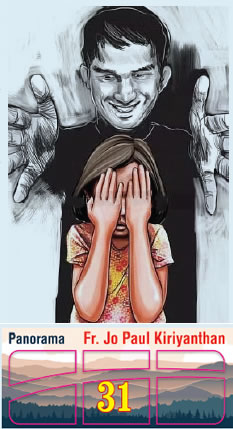

Psychodynamic theories portray the human struggle to fulfill the primal desires of id and the moral authority of superego. They say that sexual aggressors like child sexual abuse offenders lack a strong superego and are overwhelmed by their primal id (John Jay College of Criminal Justice, 2004, p. 164). Sexual desires, intimacy needs and aggression are central to their primal id. Sexual desires sometimes incorporate the need for power and control. Self-esteem problems will enhance these needs. The need for power and control over members of the opposite sex can also be expressed as indifference towards them or in the form of a sexual relationship with more vulnerable or younger members, when the offenders find gratification of the need for power through sex (Marshall & Barbaree, 1990, pp. 263–265). Some find it difficult to express anger and hostility, which builds up until it explodes, possibly in front of a child victim. Here, emotional problems and their frustration lead them to a sexual offence like child sexual abuse (Lanning, 2010, p. 37).

Some integrated theories have incorporated various etiological theories on child sexual abuse offenders within a framework. D. Finkelhor presents a ‘precondition model theory’ with four factors. First, the offender finds an ‘emotional congruence’ with a child as if the child fulfils a particular need of the offender. Then he experiences ‘sexual arousal’ by that child. At the same time he experiences a ‘blockage’ to gratifying his sexual needs in conventional ways with peers or without the use of force. Finally, there is a ‘process of disinhibition’ from one’s own internal inhibitions related to moral teachings and fear of being caught; external inhibitors like supervision and protection by other adults; and the resistance, suspicion and discomfort of the child. Alcoholic intoxication or various rationalizations play a big role in undermining such inhibitions (Finkelhor, 1999, p. 105-106). Another integrated theory is the ‘sexual abuse cycle’, which says that a predictable pattern of negative feelings, cognitive distortions and control-seeking behaviours leads to a sexual offence. It can be understood in three phases: precipitating, compensatory and integration. The precipitating phase involves exposure to a stressful event, negative interpretation of the event and coping through avoidance. In the compensatory phase, the individual tries to increase self-esteem and reduce anxiety through power-based compensatory behaviours. In the third integration phase, the individual rationalizes his offending behaviour to avoid self-depreciating and humiliating feelings (Burton, Rasmussen, Bradsaw, Christopherson, & Huke, 2014, p. 25).

No comprehensive theory adequately explains either the motivational factors or the sustaining factors of a child sexual abuse offender’s sexual behaviour (The John Jay College of Criminal Justice, 2004, p. 163). The distinctiveness would be more useful than the comprehensiveness in this context. More researches among offenders would bring further lights.